|

| Gonzalo Medina displays a poster about La Ciclovia. |

When Medina, then an official with Bogotá's transit department, returned home, he convinced city officials to try the same experiment on the Circunvular, the avenue running along the city's Eastern Hills. But after police complained that the closed road blocked access to a hospital, the new experiment called La Ciclovia was shifted to Ave. Septima.

When Medina, then an official with Bogotá's transit department, returned home, he convinced city officials to try the same experiment on the Circunvular, the avenue running along the city's Eastern Hills. But after police complained that the closed road blocked access to a hospital, the new experiment called La Ciclovia was shifted to Ave. Septima.One of Medina's goals even back then was to change the bicycle's image.

"Riding a bike was not only in bad taste," he said, but cyclists were seen "as people who couldn't afford a Renault."

"Riding a bike was not only in bad taste," he said, but cyclists were seen "as people who couldn't afford a Renault." |

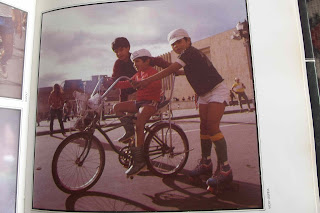

| La Ciclovia way back when. |

|

| A scene on La Ciclovía today. |

|

| Participants in a mass aerobics class, called La Recrovia. |

The idea has also expanded across Latin America and into the United States, altho Colombia's version is still the largest and most frequent. There's even an International Network of Ciclovias organization to promote the concept. La Ciclovia, along with the TransMilenio express bus network and the city's bike lane network, once gave Bogotá a reputation for progressiveness and urban ingenuity, altho that image has since faded.

Medina says the biggest improvement to La Ciclovia over the years was Mayor Enrique Peñalosa's addition of the annual Ciclovia Nocturna, or night-time Ciclovia.

But the Ciclovia Nocturna happens only once a year, and part of its route is so packed with pedestrians that you can't ride a bike.

But the Ciclovia Nocturna happens only once a year, and part of its route is so packed with pedestrians that you can't ride a bike.More important, it seems to me, is the way that La Ciclovia's become an essential Bogotá institution.

Various studies have found that the Ciclovia concept benefits not only participants' health, but also the economy, by saving on medical expenses.

"I'm proud," Medina says of his work. "It was an important contribution."

In Havana, Cuba, where Medina's wife works for the Colombian embassy, and where he says biking is risky, he continues pushing for better cycling conditions.

But to get more people onto bicycles, Medina believes that bikes mustn't be seen any longer as the 'poor man's vehicle.' In Bogotá, most bicycle commuters are still low income people who ride bikes to save on bus fare. In Colombia's class-conscious culture, the middle class and wealthy want to be seen in cars - even if that means spending hours trapped in traffic jams.

"There should be executives on bikes, so that the bike has status," Medina says.

"There should be executives on bikes, so that the bike has status," Medina says.Medina also advocates more space for pedestrians and cyclists, including car-free streets in the historical center.

Those measures would help Bogotá fulfill more of La Ciclovia's potential - to get Bogotanos to use their bikes not only on Sundays, but every day.

See some videos of Mr. Medina commenting, in Spanish, here, here, here and here.

By Mike Ceaser, of Bogotá Bike Tours